An Un-natural ‘Natural’

An Un-natural ‘Natural’

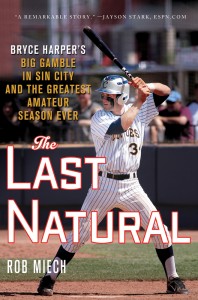

A review of The Last Natural: Bryce Harper’s Big Gamble in Sin City and the Greatest Amateur Season Ever by Rob Miech. Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2012. 356 p. Review copy courtesy of the publisher.

The title ‘The Last Natural‘ packs a lot of meaning and connotation into a few words. While ‘natural’ clearly refers to the inherent talent that Bryce Harper seems to have, there are a few other connotations, at least in baseball. Since Harper arrives at what might be considered the end of the “steroid era,” it could be a kind of pessimistic reference to Harper’s eschewing drugs since ‘natural’ can also mean pure or unchanged. It could also be a nod to Bernard Malamud‘s novel The Natural, perhaps the finest work of fiction about baseball and the source for the Robert Redford film of the same name.

But the suggestion that Harper is a ‘natural’ is hardly frivolous, despite the hyperbole in the rest of the title. Bryce Harper does have talent; he is ‘a natural’ if you will. Like Roy Hobbs, the main character in Malamud’s novel, Harper is stunningly good. But unlike Hobbs, Harper’s talents were noticed early. Scouts began watching him at age 12. At 16, in 2009, he made the cover of Sports Illustrated, the first high school baseball player to make the cover in 20 years and one of just 13 high school athletes who have ever made the cover of the weekly.

But the suggestion that Harper is a ‘natural’ is hardly frivolous, despite the hyperbole in the rest of the title. Bryce Harper does have talent; he is ‘a natural’ if you will. Like Roy Hobbs, the main character in Malamud’s novel, Harper is stunningly good. But unlike Hobbs, Harper’s talents were noticed early. Scouts began watching him at age 12. At 16, in 2009, he made the cover of Sports Illustrated, the first high school baseball player to make the cover in 20 years and one of just 13 high school athletes who have ever made the cover of the weekly.

Then, he and his parents decided to make a controversial move, one not envisioned in Baseball’s recruiting rules. Perhaps after a suggestion from super agent Scott Boras, Harper quit High School, passed his GED, and enrolled in the College of Sourthern Nevada, following his older brother Bryan, who had been recruited to play baseball there. After playing for just a year, Bryce was then, under Baseball’s rules, eligible for the draft. He was drafted 1st overall in 2010 and signed with the Washington Nationals for a $10 million contract.

But, despite all the hype, the attitude of major league clubs, outside of their scouts, is one of ‘wait and see.’ “And it’s not a knock on Bryce,” said Dick Scott [former major leaguer and father of one of Harper’s teammates]. “The SI story got his name into a lot of clubhouses. People at the major league level, their reaction is… whatever. They see great players every day. To be impressed with a high school kid that is being copared to the next LeBron James… okay. As soon as he gets here and starts proving it, great. Until then, it’s not a story.”

But his potential is why every Mormon may eventually know Harper’s name: If he lives up to his potential (a big if, I admit), he could be among baseball’s greatest players… ever. He is starting younger than almost everyone (except for Mantle and a handful of others), so he could play longer, and his skills have led to astronomical expectations. Best of all, for Mormons, he is an active LDS Church member who is clean—his talent doesn’t come from a pill bottle or cream.

The problem with all of this (calling an athlete ‘natural,’ putting a high school student on the cover of a national magazine) is that it creates expectations and puts tremendous pressure on a youth hardly old enough to cope with that pressure. In some cases, this pressure leads to promising young athletes failing to perform as expected, perhaps due to psychological stress, or to the athlete acting out in various ways—promiscuous behavior, entitlement and contempt for others are hardly unusual among ahtletes even when adults, let alone when they are so young. Youth need time to mature.

But Harper’s parents and coach justify the move because Harper needed the challenge:

“He could hit .700 in high school and regress,” [CSN coach Tim] Chambers said. “He’d get bored with the game being so easy. He needed a challenge. This was his only option.”

And, they argue, if you aren’t involved in the situation, how can you know what’s best? “It’s so easy for outsiders… who do not know Bryce and have no idea what he or his parents were about…”

Our society tends to want, if not expect, perfection from our athletes, both on an off the field. Of course, most of us realize that this desire is both unrealistic and even harmful in some cases. None of our athletes are perfect. We all know about the worst cases, from Ty Cobb to Tiger Woods, but even the most beloved athletes often have shady sides. Babe Ruth was hardly free of error. Michael Jordan is known for his peccadilloes. And the Mormon public can be just as demanding, expecting Mormon athletes to be not only good, but also faithful LDS Church members. One comment I read on a baseball site post on Mormons in baseball wanted to exclude a number of Mormons because they weren’t ‘real’ LDS Church members; they were inactive. In addition, we expect exceptional athletes who are also fair on the field and kind off the field—almost the opposite of the stereotypical player of ‘Church ball.’ Perhaps our expectations are too often unreasonable.

In ‘The Last Natural,’ Miech traces the single season that Bryce Harper spent in junior college at the College of Southern Nevada, a season in which Harper adjusts to a higher level of play than he saw in High School and to a higher level of attention. Starting the year stressed out and underweight from an overly ambitious prep schedule of at least 160 games, including his high school games, club teams in Las Vegas, Southern California, Arizona and Oklahoma and a spot on the U.S. eighteen and under national team, Harper was rested and protected from much of the attention by a wise coach while he developed and contributed to his teams bid for the Junior College World Series.

Despite the potential dramatic arc of the CSN games as the team moved toward the championship, The Last Natural is more about Harper, his team mates and his coaches than it is about the games. Miech writes about what makes these people think and act as they do, and how they interact with Harper, instead of who made what play in which game during that season. The principle issues in the book aren’t baseball skills or mental preparation as much as how this group manages under a microscope and what the after-effects are from the Harper family’s decision to make a controversial move. Miech never tries to construct any formal argument for or against Harper’s decision, but he provides a lot of ammunition for those who want to explore the issue of pressure and maturity to play professional sports.

Those, Mormon or not, who are looking for perfection from Harper or his team mates or even his coaches and parents and the other adults around them are likely to be quite disappointed. There are no clear heroes here. There are people; good people with flaws who struggle to reach their goals and get along with others and yes, even people looking for the fame and fortune that can happen after you appear on the cover of a national magazine.

Both on and off the field Harper is impressive, but he is no saint. His performance on the field can be inconsistent at times, but his very high expectations of himself never are. Nor is the intensity with which he plays. Harper describes it this way:

“… I’m an ______ on the field. I’m not going to lie. I’m an _______. I’m a ____, in the aspect that… I don’t talk ____ or crap about anyone, but if you’re a ____ to me, I’ll be a ____ back. I’m going to try to ram it down your throat, hit a bomb, and say, ‘Gotcha! There you go! Shut up!’ But I won’t ever taunt or anything. I haven’t taunted anyone this season. I never [verbally] taunted anyone this year, not once.”

At one point in the book, his teammates made fun of this intensity:

“Harper’s teammates mimicked his walk, the way his weight instantly shifted forward to the balls of his feet when he took a step. He always seemed to be leaning forward. Perpetual aggression.”

This has led to frustration when he doesn’t perform—he threw his batting helmet so much during the season described in the book that it broke; he regularly shattered bats — once by slamming his bat into home plate after striking out; and he nearly bathed others in the dugout in gatorade when he took out his frustrations on the cooler. Miech sees this as evidence of the pressure that Harper puts on himself:

“But after flying out to right in the third, Harper sat on the bench, tormented once again, with his head in his hands, once again, and stared at the ground. The pressure he put on himself, every time he grabbed a bat, was indescribable. Forget the words of any critic, scout, recruiter, or opponent; if Harper did not do something thrilling almost every time he stepped to the plate, in his mind something was terribly wrong. He was inconsolable.”

But at a crucial point during the season, CSN coach Tim Chambers told him to stop—and he did—and he apologized, personally and humbly, to his coach for his behavior:

“Those [text] messages were big,” said teammate Gabe Weidenaar. “He’s a Sports Illustrated cover boy and he apologized to [coach] Chambers? That’s huge on his part. Anyone else in his shoes could be, like, ‘___ off, I don’t need you at all.’ That says something.”

His intensity often comes off as cockiness or arrogance. At one game Miech overhears two high school players watching Harper say to each other, “Is that Bryce Harper on deck?” followed by the reply, “Don’t you see God above his head?” But an opposing coach put a different spin on his attitude:

“He’s a pretty confident kid. I don’t mind it. Whether or not he produces that day, he knows he’s good. I want players like that. I want players who don’t know any better, to play with arrogance. Its different playing with arrogance and being a bad kid… if it’s a kid who didn’t produce and wasn’t a good teammate, he’s embarrassing himself. I like kids who don’t know any better. ‘I’m better than this guy and I’m going to walk with a swagger.’ I find nothing wrong with that. I admire that.”

Assistant coach Marc Morse says that this mentality is what gives Harper his potential:

“Wait until he’s nineteen or twenty, when he has two or three more years under his belt. You might see the next .400 hitter. Then he’ll be thinking, once he does hit .400, about .500. Why not? He’ll think, ‘Why can’t I?’ That’s what’s scary about the kid. He’s honestly trying to break the mold, the thought process of history in this game that says .300 is good. He says, ‘________, .400 is good. And you know what? I’ll do .500.’ Watch. Boy, you can’t ask for a better mentality.”

This mentality can be seen in every play he makes—running out the fly ball or ground ball that seems like an easy out. He tries to get to second base by the time his home run clears the wall: “My dad taught me that. I sprint around the bases. No pimp walk.”

Off the field his mentality is likewise admirable. One assitant coach sees his responsibility in the fact that he patiently signs autographs when so many major leaguers blow-off fans, “Bryce gets who he is and he understands the responsibility to the game and the people, who will eventually be paying [his] salary.” Teammate Casey Sato agrees, “The things he goes through on a day-to-day basis are completely unreal, but he responds in such a classy way. People need to get off his back and understand he’s only seventeen. It’s amazing. He’s just a good person, a good kid, and he should be completely respected for what he does for other people.”

Perhaps Harper’s flaw lies in his arrogance, passion and frustration when he doesn’t live up to his own expectations. Throughout the book CSN coach Chambers countered this view with the fact that often gets lost when observers see Harper as the giant among his peers: he was only 17! Even today, two years after the events of this book, when Harper gets frustrated playing in the majors, as he did recently, and slams his bat into a wall catching the rebound above his eye (which required 10 stiches), I can hear his coach’s and teammates’ words echo: he’s only 19! Give him a chance to mature. And once again we return to the crucial issue for young athletes like Harper: maturity. When is too young?

Many Mormon readers will be happy with Harper. He has all his bats inscribed with “Luke 1:37” (For with God nothing shall be impossible). One teammate, Casey Sato, who is a returned LDS missionary, observes that this isn’t just show:

“Those scriptures, they’re not a lie. He doesn’t put them on there because that’s what Tim Tebow does… Bryce does that because he actually knows it.”

Harper also makes clear that he will wear his religion on his sleeve:

“I want to be a leader and I want everyone to know ‘he’s a good Mormon boy,’ not just a baseball player. I’m strong about God in my life. Definitely, few people know I’m Mormon and I talk about God.”

Perhaps reflecting our religion, Harper also doesn’t have the materialistic attitude so common among well-paid professional athletes. Teammate Tyler Hanks (from Spanish Fork, Utah, but apparently not LDS) was surprised when Harper told him he wouldn’t buy a new car when with his first professional paycheck. “Harper told him the dependable Toyota Tacoma with six figures in mileage worked just fine.”

The season makes clear that Harper’s Mormonism is clearly part of who he is. Miech reports an off-the-cuff conversation between Harper and a teammate before a banquet about Harper’s tie. “That a clip-on?” asked the teammate. “C’mon, bro,” said Harper, surprised his teammate would think he didn’t know how to tie a tie. “I’m Mormon.” Reading this book, its not hard to expect that Harper will one day be speaking at LDS youth events.

But other elements of Harper’s personality and actions may lead to questions among LDS Church members. At least as portrayed in the book, he has a bit of a potty mouth. Perhaps worse, while Harper several times passes on alcohol and cigarettes in the book, his definition of the Word of Wisdom seems to allow him to use chewing tobacco. This use is a bit of a theme in the book, since chewing tobacco is against NCAA rules, which leads the author to assist some members of the team in hiding their chew from coaches and game officials.

Early in the book, Miech addresses the possibility that Harper might serve an LDS mission. The answer to his question came from Harper’s grandfather, Jim Brooks, in almost stengalese fashion:

“… There is something waiting for him. In the church, missions are common. Well, Bryce’s mission is right out there.”

Brooks pointed to the outfield.

“He’s going to do more for young people and young kids than any of us would ever think of doing, because of how he does things… pictures he takes with his head bowed. That, to me, will be more of a help to young kids than anything in the world, because of his religious background. Religion is a funny thing to talk about. You have to have something. If you don’t have something, you don’t have anything your whole life.”

A few pages later, Miech indicates that Harper agrees. But given his tendency to temper tantrums when he doesn’t perform as he wants to, many Mormons might assume that he would benefit from the maturing that a mission would provide. Perhaps. But those around him, parents, team mates, coaches, continue to point out in the book that Harper is mature… at least for his age (although not in every way).

Beyond the comparison of Bryce Harper to Malamud’s Roy Hobbs, the title The Last Natural also invites the comparison of the book itself to Malamud’s novel. Unfortunately, the comparison is not at all flattering for Miech. I found the prologue to be a confusing jumble, with no coherent line of thought. At times I had to read sentences twice or three times to understand what Miech was trying to say. I was not always successful. The writing lacks the clarity needed in a non-fiction book like this. Perhaps this level of editing is what we must expect today in what might be called “low-brow” books. Fortunately, as the book progressed, I was able to get used to these problems and could still enjoy the book.

Despite this qualitative problem, the topic is timely. For Mormons, this book is useful in understanding Harper, who has the potential to displace Steve Young, Danny Ainge and perhaps even Jimmer Fredette in U.S. Mormon culture. More importantly, regardless of your religion, The Last Natural provides an introduction to the difficult issue of maturity in professional sports, an issue that will, I think, remain controversial.

[For the Mormon audience, I should add that, following journalistic practice, Miech reports conversations word for word, expletives and all. I have rendered them as ___ above. Given the silliness of the LDS market, this likely means that you won’t find this book in Deseret Book or other LDS bookstores.]

Note: I have cross-posted this review to Times and Seasons.

I should add that the chewing tobacco Bryce uses in the book is the (I gather) weak flavored stuff that’s more like chewing gum. When he does finally try the stronger stuff at the suggestion of a teammate, he doesn’t like it, saying “one and done.”

Great site. Lots of helpful info here. I am sending it to a few buddies ans additionally sharing in delicious. And obviously, thank you on your sweat!

Thanks, Kendrick. I’m glad you like the site. Please come back again!